Stop the veggie burgers!

Complete streets are an accessibility issue. Pretending otherwise denies the experience of thousands of local residents.

Our streets should be accessible for everyone.

Image credit: J. Kanner

I don’t really like Impossible Burgers. I think they taste funny.

But when restaurants include vegetarian options on their menu, it makes those businesses more inviting for vegetarians, so they can end up serving more people.

When buildings include ramps or elevators in addition to stairs, it makes the facility accessible to more people.

When signs and instructions are written in multiple languages, it makes the message available to more people.

In today’s world, most people prefer our restaurants, libraries, and schools to be accessible to a wide range of people. Vegetarian options, wheelchair ramps, and inclusive policies are all good examples of things that make a place more accessible and welcoming to a wide range of people.

In general, creating more options for access and inviting in more people is the American way when designing public spaces and when we think about our businesses and institutions.

Our transportation system, though, is a strange exception to this. For some reason, public officials often prefer LESS accessible streets, with FEWER options for who can use them and how. Even baby steps toward making our streets more diverse leads some people to complain.

Honestly, a lot of people talk about bike facilities as if the people who use them either don’t exist or don’t deserve to move around the city. This is especially offensive when we consider that many people riding bikes in Pasadena don’t have access to a car, because they are low-income riders, they’re too young to drive, or they’re unable to drive for other reasons. One study reported that as many as 40% of people biking in Los Angeles earn less than $15,000 a year. In the state of California, around 20% of the population is too young to drive, and another 12% are adults who don’t have a driver’s license. More than thirty percent of people in Pasadena don’t drive! We should be moving in a direction that recognizes this diversity of road users, and build our streets to be more inclusive.

In an earlier blog post, I detailed how 99% of our street space is used for moving and parking cars, a choice that mostly excludes people riding bikes, scooters, or other mobility devices. Pasadena has over 900 miles of lanes for moving cars, but only 3 miles of protected bike lanes. In Pasadena, car lanes outnumber protected bike lanes by 300-to-1. Imagine a restaurant with a menu of 300 meat options, and only 1 vegetarian option; that’s our street system today. Drivers have more options than the menu at Cheesecake Factory.

And yet, against all logic and reason, the Mayor of Pasadena is complaining that the new cycle track on Union Street – Pasadena’s only protected bike lane – is somehow a problem. There has been no significant increase in traffic since the cycle track’s construction, so the mayor’s position is very troubling. Here’s a recent quote:

“… we've gotta be careful about that, now that we've seen what's happening on Union Street. We were told there would be hundreds and thousands of bicyclists going back and forth—that's— that's not what we've seen. I intend to maintain the position that we need to revisit that plan.”

As a person who uses the Union Street bike lane routinely, imagine how that sounds to me! What if we take this same line of thought, and apply it to questioning the value of a wheelchair ramp:

… we've gotta be careful about that, now that we've seen what's happening on [the new wheelchair ramp]. We were told there would be hundreds and thousands of [wheelchair users] going back and forth—that's—that's not what we've seen. I intend to maintain the position that we need to revisit that plan.

A well-designed bike lane network can increase the accessibility of Pasadena without detriment to other modes of travel. In other cities, adding bicycle facilities have been shown to also help drivers by reducing collisions and improving travel times.

What’s the right number of people who need to use a wheelchair ramp that justifies it being built? I think most people would say that adding a wheelchair ramp creates more options, and so makes a building more accessible. If even one person uses a wheelchair ramp, then it makes the building better—right? Why don’t city officials have a similar feeling about creating options for safe transportation?

In this video, Mayor Gordo explains that I don’t exist.

Here’s another quote from Mayor Gordo that I found troubling:

“Because when was the last time that anybody here rode their bike to the grocery store? And now imagine pedaling back up North Lake Avenue with your groceries in tow ... it's not going to happen. And so, we've gotta be careful with our built infrastructure, and making mistakes.”

For me, this was a hurtful argument. I ride my bike to the grocery store (and the hardware store, and the library, and everywhere else) routinely. I go up hills easily because I ride an e-bike. Does the Mayor think that I don't matter? Imagine if that same dismissive tone was applied to a person with a different mobility device:

“Because when was the last time that anybody here [took a walker] to the grocery store? And now imagine [using your walker to get] back up North Lake Avenue with your groceries in tow ... it's not going to happen. And so, we've gotta be careful with our built infrastructure, and making mistakes.”

People who get around with walkers and bikes buy groceries!! It’s as if the speaker wants to close his eyes and make people who use mobility devices disappear.

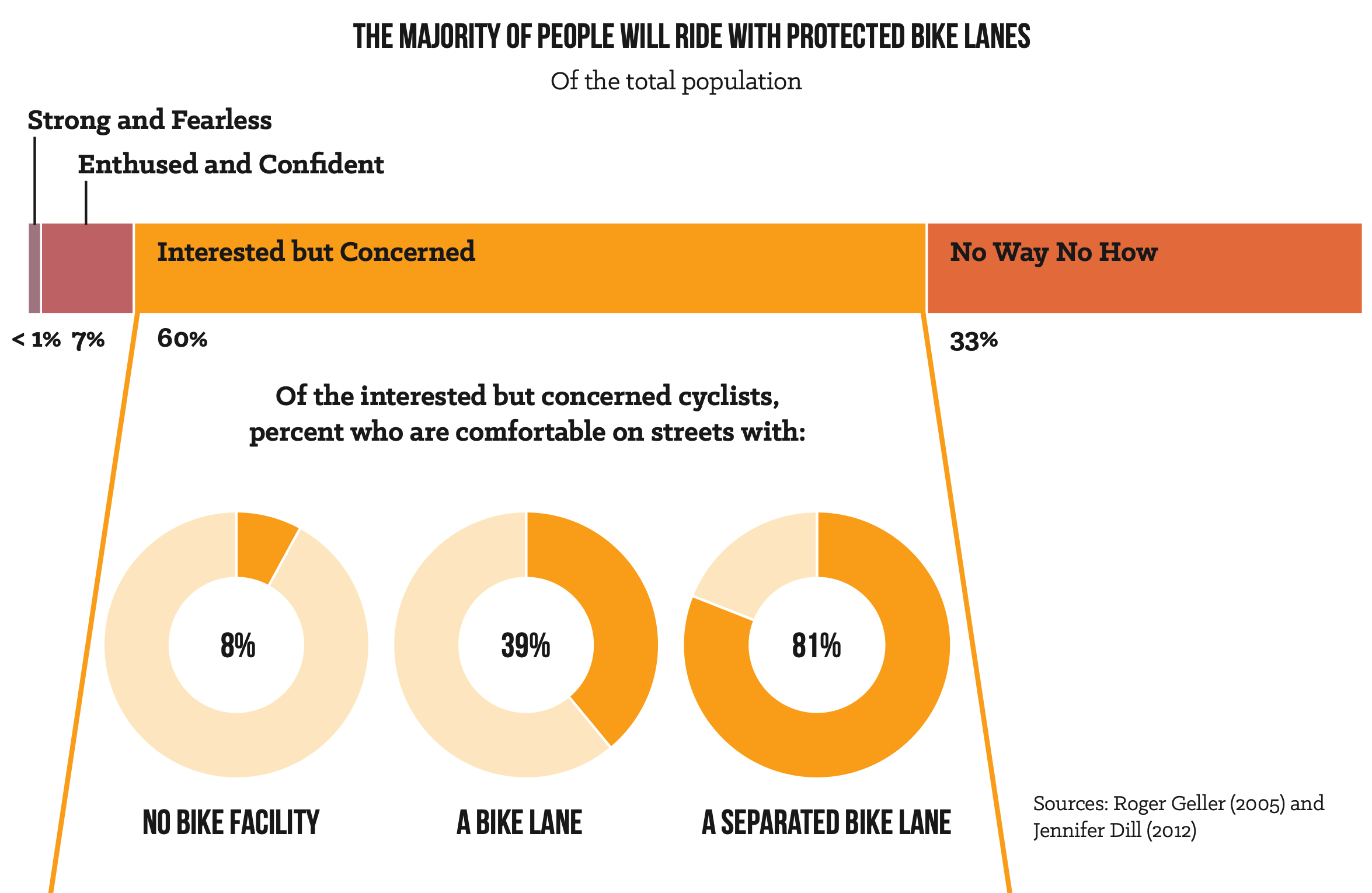

The truth is there are thousands of people today using bikes, scooters, and all types of both human-powered vehicles and mobility aids to move around Pasadena. If you go out for lunch, notice that the bike racks near restaurants are often full, in part because staff members at the restaurant are biking to work. We also know from national surveys that there are thousands more people who WOULD ride bikes in Pasadena, but can’t or won’t because they don’t feel safe doing it. Cities that build safe biking infrastructure consistently see increases in the rates of ridership, proving that a lack of safe facilities is keeping people stuck in their cars or waiting for the bus.

In national surveys, people consistently report that safety concerns related to car traffic is the number one deterrent to riding a bike. Over half of Americans report they would ride a bike more often if they had access to a network of protected bike lanes. Image Credit: NACTO Bike SHARE Equity Practitioners’ Paper #3

It is backwards for the Mayor to argue that the Union Street bike lane should be “revisited” because he is concerned about low ridership. Currently, there are no truly safe bike routes that access the Union Street bike lane, so how are safety-conscious riders supposed to reach it? Clearly, if the goal is to increase ridership in Pasadena, we should be building more safe places to ride, not less.

I ride a bicycle every day in Pasadena, often with my 12-year-old son. Safe facilities for my son and me make a big difference in our daily lives. For example, the new bike lanes on Cordova Street and Union Street are making it easier and safer for us to move around the city. I use the new bike lanes routinely to get my son to school, to get myself to work, and to go out for lunch. Restaurants that I’d never thought to try before - like Chim! Thai at Union and Lake - are suddenly convenient to reach. They also make it easier, faster, less stressful, less dangerous, and just more convenient to reach any number of places. I can’t tell you how many HOURS I’ve spent staring at Google Maps, trying to find winding routes across Pasadena that avoid big, scary roads full of fast-moving cars. Having even a small number of well-designed bike lanes reduces the planning time and makes these trips feel fast and easy.

Imagine then, what it feels like to hear city officials dump on these improvements and complain that they are somehow a problem. Adding a bike lane to a street doesn’t stop drivers from reaching their destination, any more than offering a veggie burger prevents diners from ordering a steak. I think we would talk about bike lanes in a different way if we understood them as providing critical access to the city rather than as an “extra” that we might include, or not.

I have a friend in Pasadena with a medical condition that prevents her from driving. She is a single mom with teenage daughters. When her girls were in middle school, there was no easy way for her to get them to school. The two-mile trip up Lake Avenue to Eliot Middle School was too unsafe for the girls to do on their own by bicycle, and their apartment didn’t have secure bike parking. Instead, they relied on the public bus system when they could, and paid for Ubers they could barely afford when the bus schedule didn’t work. The biking facilities that could have gotten her girls to school simply didn’t exist.

For kids going to school, for low-income people who can’t afford cars, and for anyone else who prefers two wheels over four, we should be building our streets to be accessible and inclusive. Instead, too often, public officials describe bike facilities as “extras,” and discuss them from the perspective of people who don’t plan to use them. Instead, we should understand bike infrastructure as a necessity that provides access for thousands of people and that costs people time, money, and stress when it is missing.